For the time being, uncertainty will probably hang around like a dark cloud over markets. But that doesn’t mean you should head for the hills.

The global economy has started to stagger. Earlier this week, the U.S. stock market tumbled after a historically reliable predictor of recessions flashed a warning signal.

Some of the world’s largest economies are either slowing or contracting, including China, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Clearly, there’s a lot going on around the world.

What’s a yield curve? And why should I care?

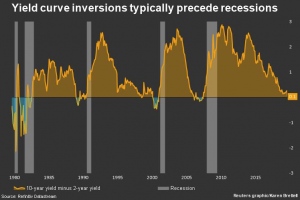

The stock selloff on Wednesday was caused by a development in the bond market called a yield curve inversion, which means that the yield–or return–on short-term U.S. bonds exceeded that of long-term bonds. The government needs to pay out higher rates of interest to attract investors to its long-term bonds. The usual pattern is the longer-dated the bond, the higher the yield. But with so many losing confidence in the near-term prospects of the economy and rushing to buy longer-term bonds as a safe haven, investors crowded into bonds, driving up their price and pushing down the yield on the 10-year Treasury note (bond prices and yields move in opposite directions). The result: the U.S. government is now paying more to attract buyers to its 2-year bond than its 10-year bond. This is significant. It suggests that investors are nervous about the immediate outlook for the economy.

This is the first time the 10-year yield has fallen below the 2-year yield since 2007, just before the Financial Crisis. That’s what really spooked investors this week. Plus, that inverted yield curve has preceded every recession in the past 50 years. (It’s also incorrectly signaled a recession or two in the past that never actually happened, so it’s not a perfect predictor.) Regardless, yesterday’s yield curve inversion is the latest in a series of news items that have market watchers worried.

This is the first time the 10-year yield has fallen below the 2-year yield since 2007, just before the Financial Crisis. That’s what really spooked investors this week. Plus, that inverted yield curve has preceded every recession in the past 50 years. (It’s also incorrectly signaled a recession or two in the past that never actually happened, so it’s not a perfect predictor.) Regardless, yesterday’s yield curve inversion is the latest in a series of news items that have market watchers worried.

But should they worry? The U.S. seems to be a bright spot in the global economic picture. Some European countries actually have negative bond yields, which means that people are paying governments to hold their money for them. U.S. bonds offer some of the best yields in the developed world, despite their recent drop. With bond yields at multi-year lows, many investors say that there are no good alternatives to U.S. stocks for those seeking returns. The S&P 500 boasts a dividend yield of 2%, which is well above the 1.528% yield on the 10-year Treasury note (as of this writing).

Markets tend to keep moving higher immediately following a yield curve inversion. Since 1978, the S&P 500 has risen an average of 13% from the first time the spread inverts on a closing basis to the beginning of a recession, according to Dow Jones. Since 1956, past recessions have started on average around 15 months after an inversion of the 2-year and 10-year yields. Of course, past performance cannot guarantee future returns.

Recession on the horizon?

No one knows if these bond market signals mean that an economic crisis is coming. But what’s clear is that the global economy is slowing. No need to worry, though — this is a perfectly natural thing, and you could be rewarded by staying invested in this market.

Research shows that although there have been 11 recessions–commonly defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth–since World War II, only three of them triggered particularly severe market downturns: 1973-1975 (market decline of 48%), 2000-2001 (market decline of 49%), and 2008-2009 (market decline of 56%).

Looking at the causes of each of those recessions/bear markets, each of them followed a unique series of circumstances in economic history. The 1973 recession was triggered by an oil embargo targeting the United States, and the 2000 and 2008 recessions were largely due to bubbles in the internet and housing sectors. Unlike the other eight recessions since WWII, each of these three events was caused by large imbalances in the economy. The majority of recessions, however, were natural slowdowns in the business cycle, and the corresponding market sell-offs were relatively less severe.

Should we assume that the next recession that comes along will be like the “normal” ones and not like the three big ones? Some say that right now, the U.S. economy doesn’t have the same types of imbalances that led to the three outliers. If we go with the odds and take the viewpoint of the majority, the next recession will probably be more like the garden variety kind we’ve seen historically. That would mean a market downturn that’s not as severe as others in recent memory.

What does all this mean for the stock market?

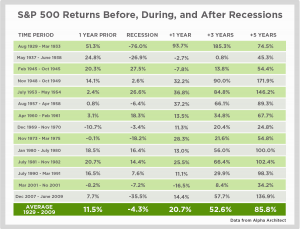

It could also mean that investors will be rewarded for their patience. Here’s what total returns for the S&P 500 looked like leading up to, during, and after each recession from the Great Depression onward: (click the table to enlarge)

Contrary to what you might think, stocks actually rose during half of the last 14 recessions, and they were positive in 11 out of the 14 years leading up to a recession. The stock market was down a year later only three times following a recession. In general, stocks tend to perform about average in the year leading up to a recession, below average during a recession, and above average in the one, three, and five year periods following the end of a recession.

What should I do?

We don’t know when a recession has actually started until the National Bureau of Economic Research makes the call, which is often after we’re almost finished with or have already exited a recession. Investors need to keep investing during these periods of volatility in order to capture the market upturn.

We’ll go into another recession at some point. And it’s possible that stocks could show underwhelming performance when it happens based on the strong gains U.S. stocks have shown over the past several years. But it’s also possible they won’t. Nobody knows.

For the time being, uncertainty will probably hang around like a dark cloud over markets. But that doesn’t mean you should head for the hills. Recessions and bear markets are inevitable, but you can put yourself a better position by staying the course.

At Azzad, we strive to help you balance these short term fears with your long term goals so you can stay comfortably committed to your investment plan. If you’re feeling fearful, give us a call at 703-207-7005.

Staring down the yield curve

Staring down the yield curve

The global economy has started to stagger. Earlier this week, the U.S. stock market tumbled after a historically reliable predictor of recessions flashed a warning signal.

Some of the world’s largest economies are either slowing or contracting, including China, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Clearly, there’s a lot going on around the world.

What’s a yield curve? And why should I care?

The stock selloff on Wednesday was caused by a development in the bond market called a yield curve inversion, which means that the yield–or return–on short-term U.S. bonds exceeded that of long-term bonds. The government needs to pay out higher rates of interest to attract investors to its long-term bonds. The usual pattern is the longer-dated the bond, the higher the yield. But with so many losing confidence in the near-term prospects of the economy and rushing to buy longer-term bonds as a safe haven, investors crowded into bonds, driving up their price and pushing down the yield on the 10-year Treasury note (bond prices and yields move in opposite directions). The result: the U.S. government is now paying more to attract buyers to its 2-year bond than its 10-year bond. This is significant. It suggests that investors are nervous about the immediate outlook for the economy.

But should they worry? The U.S. seems to be a bright spot in the global economic picture. Some European countries actually have negative bond yields, which means that people are paying governments to hold their money for them. U.S. bonds offer some of the best yields in the developed world, despite their recent drop. With bond yields at multi-year lows, many investors say that there are no good alternatives to U.S. stocks for those seeking returns. The S&P 500 boasts a dividend yield of 2%, which is well above the 1.528% yield on the 10-year Treasury note (as of this writing).

Markets tend to keep moving higher immediately following a yield curve inversion. Since 1978, the S&P 500 has risen an average of 13% from the first time the spread inverts on a closing basis to the beginning of a recession, according to Dow Jones. Since 1956, past recessions have started on average around 15 months after an inversion of the 2-year and 10-year yields. Of course, past performance cannot guarantee future returns.

Recession on the horizon?

No one knows if these bond market signals mean that an economic crisis is coming. But what’s clear is that the global economy is slowing. No need to worry, though — this is a perfectly natural thing, and you could be rewarded by staying invested in this market.

Research shows that although there have been 11 recessions–commonly defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth–since World War II, only three of them triggered particularly severe market downturns: 1973-1975 (market decline of 48%), 2000-2001 (market decline of 49%), and 2008-2009 (market decline of 56%).

Looking at the causes of each of those recessions/bear markets, each of them followed a unique series of circumstances in economic history. The 1973 recession was triggered by an oil embargo targeting the United States, and the 2000 and 2008 recessions were largely due to bubbles in the internet and housing sectors. Unlike the other eight recessions since WWII, each of these three events was caused by large imbalances in the economy. The majority of recessions, however, were natural slowdowns in the business cycle, and the corresponding market sell-offs were relatively less severe.

Should we assume that the next recession that comes along will be like the “normal” ones and not like the three big ones? Some say that right now, the U.S. economy doesn’t have the same types of imbalances that led to the three outliers. If we go with the odds and take the viewpoint of the majority, the next recession will probably be more like the garden variety kind we’ve seen historically. That would mean a market downturn that’s not as severe as others in recent memory.

What does all this mean for the stock market?

It could also mean that investors will be rewarded for their patience. Here’s what total returns for the S&P 500 looked like leading up to, during, and after each recession from the Great Depression onward: (click the table to enlarge)

Contrary to what you might think, stocks actually rose during half of the last 14 recessions, and they were positive in 11 out of the 14 years leading up to a recession. The stock market was down a year later only three times following a recession. In general, stocks tend to perform about average in the year leading up to a recession, below average during a recession, and above average in the one, three, and five year periods following the end of a recession.

What should I do?

We don’t know when a recession has actually started until the National Bureau of Economic Research makes the call, which is often after we’re almost finished with or have already exited a recession. Investors need to keep investing during these periods of volatility in order to capture the market upturn.

We’ll go into another recession at some point. And it’s possible that stocks could show underwhelming performance when it happens based on the strong gains U.S. stocks have shown over the past several years. But it’s also possible they won’t. Nobody knows.

For the time being, uncertainty will probably hang around like a dark cloud over markets. But that doesn’t mean you should head for the hills. Recessions and bear markets are inevitable, but you can put yourself a better position by staying the course.

At Azzad, we strive to help you balance these short term fears with your long term goals so you can stay comfortably committed to your investment plan. If you’re feeling fearful, give us a call at 703-207-7005.

Recent Posts

Don’t Send Your Child Off to College Without These Four Tools

How To Reclaim an Inactive 401(k)

How To Estimate Your Retirement Income Needs

Volatility strikes back

Making Best Use of Your Behavioral Biases for Retirement Saving

3 Ways to Apply the 80/20 Rule to Your Financial Pursuits

Ask these 3 questions when shopping for an investment

College protestors are right. We should know what we own.

Halal fixed income investing in a ‘higher-for-longer’ market

Azzad offers condolences on the death of renowned scholar Dr. Mohamad Adam El-Sheikh